For years, science advocates and health professionals have been singling out pharmacies for giving undue legitimacy (and shelf space) to homeopathy. But the pharmacy profession can’t seem to separate itself from the sale of this profitable placebo. The issue is one of paternalism and ethics. Homeopathic “remedies” look like conventional medicine when they’re stocked on pharmacy shelves. But unlike conventional medicine, homeopathic products don’t contain any “medicine” at all. Homeopathy is fundamentally incompatible with a scientific understanding of medicine, biochemistry and even physics. Questions have been raised worldwide about the ethics of pharmacists and pharmacies selling homeopathy to consumers who may think they’re buying medicine when they’re effectively buying sugar pills. The profession has largely ignored the issue, seemingly comfortable with leaving the decision to sell up to individual stores, and dealing with homeopathy strictly in commercial terms (which, I have argued, is also unethical.) While some retail pharmacists and pharmacies refuse to sell homeopathy, the overwhelming majority of community pharmacists have allowed it to find a space on most pharmacy shelves.

Homeopathy is not herbalism

It could be that pharmacists don’t understand the facts of homeopathy. Homeopathy is often misunderstood as a natural remedy, akin to a type of herbalism. The marketing and labeling of these “remedies” encourages this perception, often describing homeopathy as a “gentle” and “natural” system of healing, and putting cryptic terms like “30C” beside long Latin names of what appears to be the active ingredients. In reality, there is little likelihood that a homeopathic remedy contains even a single molecule of any listed ingredient. So while there may be hundreds of homeopathic remedies in a pharmacy, they are chemically indistinguishable, usually containing just sugar, water, or alcohol.

As would be expected with inert products, rigorous clinical trials confirm what basic science predicts: homeopathy’s effects are placebo effects. Two of the more comprehensive reviews of the evidence are the 2010 Evidence Check from the United Kingdom’s House of Commons Science and Technology Committee and the 2014 Australian National Health and Medical Research Council review, which reached the following conclusion:

Based on the assessment of the evidence of effectiveness of homeopathy, NHMRC concludes that there are no health conditions for which there is reliable evidence that homeopathy is effective.

Homeopathy should not be used to treat health conditions that are chronic, serious, or could become serious. People who choose homeopathy may put their health at risk if they reject or delay treatments for which there is good evidence for safety and effectiveness. People who are considering whether to use homeopathy should first get advice from a registered health practitioner. Those who use homeopathy should tell their health practitioner and should keep taking any prescribed treatments. The National Health and Medical Research Council expects that the Australian public will be offered treatments and therapies based on the best available evidence.

Emphasis added.

Do regulators understand the issue?

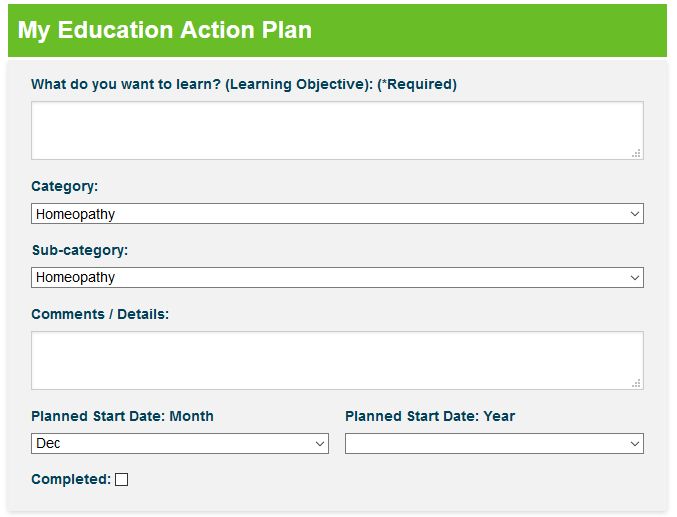

As a pharmacist, I’m responsible for my own continuous professional development and education. My provincial pharmacy regulator is responsible for ensuring pharmacists are competent, and a variety of tools are used to ensure that’s the case. I recently received a notification from my regulator that I’m required to complete a self-assessment tool as part of a quality assurance review. All pharmacists in my province are required to complete this requirement at least once every five years. In short, we must assess our own learning needs, implement a plan, and evaluate its effectiveness as it applies to pharmacy practice. We are required to document this plan, using a tool to describe our education plan. Imagine my surprise when I noticed this in the drop-down menu of categories:

Pharmacists are the health professionals with specialized training in pharmacology, and an education that concentrates on drug design, delivery and understanding how to use medicines effectively and safely. If any health professional should recognize the logical and scientific leaps that homeopathy necessitates, it should be pharmacists. So it’s obviously concerning when regulators themselves either don’t understand the issue, or don’t seem concerned about embedding homeopathy into a pharmacist’s education. While I personally believe that pharmacists need to make this change themselves (similar to how the profession has largely quit its tobacco habit), it could be that regulators are barriers, not enablers, of change.

An “unacceptable risk” in pharmacies

An independent review of Australian pharmacy practice has recommended that homeopathic products should be kept out of pharmacies that provide government-funded medications to patients. Entitled Review of Pharmacy Remuneration and Regulation, the report provides guidance to the entire retail pharmacy industry to support Australian access to safe, high-quality medicines and pharmacy care. The review is part of a broader agreement between the Australian government and the Pharmacy Guild, the national organization for pharmacists and pharmacies. Remarkably, the interim report describes homeopathy as presenting an “unacceptable risk” to consumers:

The general consensus as demonstrated by submissions to the Review and the Panel’s face-to-face consultations is that homeopathy and homeopathic products do not belong in community pharmacies. The majority of pharmacists and other stakeholders argued that these products lack any evidence base and have sufficient evidence of non-efficacy to preclude their ethical sale in community pharmacies. This is supported by the public positions of professional pharmacy bodies – for example, the PSA [Pharmaceutical Society of Australia], whose Position Statement on Complementary Medicine states: “PSA does not support the sale of homeopathy products in pharmacy.”

The only defence put to the Panel regarding homeopathy was that it was harmless and able to be used as a placebo in certain circumstances. The Panel does not believe that this argument is sufficient to justify the continued sale of these products in pharmacies that supply PBS [Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme] medicines. In particular, the Panel notes that the supply of homeopathic products through pharmacies is not benign but, rather, risks creating a perception of reliability and efficacy in the mind of the consumer based on the status of the pharmacy as a healthcare provider. This may encourage patients to choose a homeopathic product over a conventional medicine with robust evidence of efficacy, which creates a risk of harm to the patient’s health.

Its recommendation is unambiguous:

SALE OF HOMEOPATHIC PRODUCTS

Homeopathy and homeopathic products should not be sold in PBS-approved pharmacies. This requirement should be referenced and enforced through relevant policies, standards and guidelines issued by professional pharmacy bodies.

The report also give specific advice on “complementary” medicines such as supplements, recommending that they be shelved in a separate area of the pharmacy, recognizing that they are not subject to the same evidence requirements to be allowed for sale (similar to Canada and the United States):

In general, stakeholders put forward the view that pharmacists perform a valuable role in advising consumers on complementary medicines. However, there is some concern relating to the sale of products with a limited evidence base, or none at all, alongside prescription and other scheduled medicines.

Its recommendation is a compromise between access and evidentiary concerns:

Community pharmacists are encouraged to:

a. display complementary medicines for sale in a separate area where customers can easily access a pharmacist for appropriate advice on their selection and use

b. provide appropriate information to consumers on the extent of, or limitations to, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) role in the approval of complementary medicines. This could be achieved through the provision of appropriate signage (in the area in which these products are sold) that clearly references any limitations on the medical efficacy of these products noted by the TGA.

If you’re interested in commenting directly on the interim report, submissions are accepted through July 23, 2017.

Community or retail pharmacy is a unique mix of health care delivery within a private, for-profit retailer. Yet pharmacies have a specific, designated role in the health care system. For that reason, pharmacies can and should to do more than what we might expect from another retailer. Pharmacists ought to know better, and they ought to do better. It will be interesting to see the consequences of this review on the profession of pharmacy in Australia.